Reworking a long-beloved album is one of those things that artists just aren’t supposed to do. So of course, Elvis Costello went ahead and did it. In its original form, 1978’s This Year’s Model was The Attractions’ debut as a band, the source of many Costello classics, a well of lyrical venom, and a New-Wave landmark. So why not mess with it over 40 years later?

What Costello’s done with the new Spanish Model is pretty much unprecedented – the first time an artist has overseen a rework of their own album, using the original backing tracks, in a different language. He and producer Sebastian Krys, a recent Costello collaborator and multiple Latin Grammy winner, have enlisted a dream team of Spanish-singing artists – among them, Chilean pop star Cami, Argentina’s Fito Páez, and Colombia’s Juanes – to sing over the original tracks. Each was given free rein to rework melodies and rewrite lyrics, but the attitude of the original proves universal.

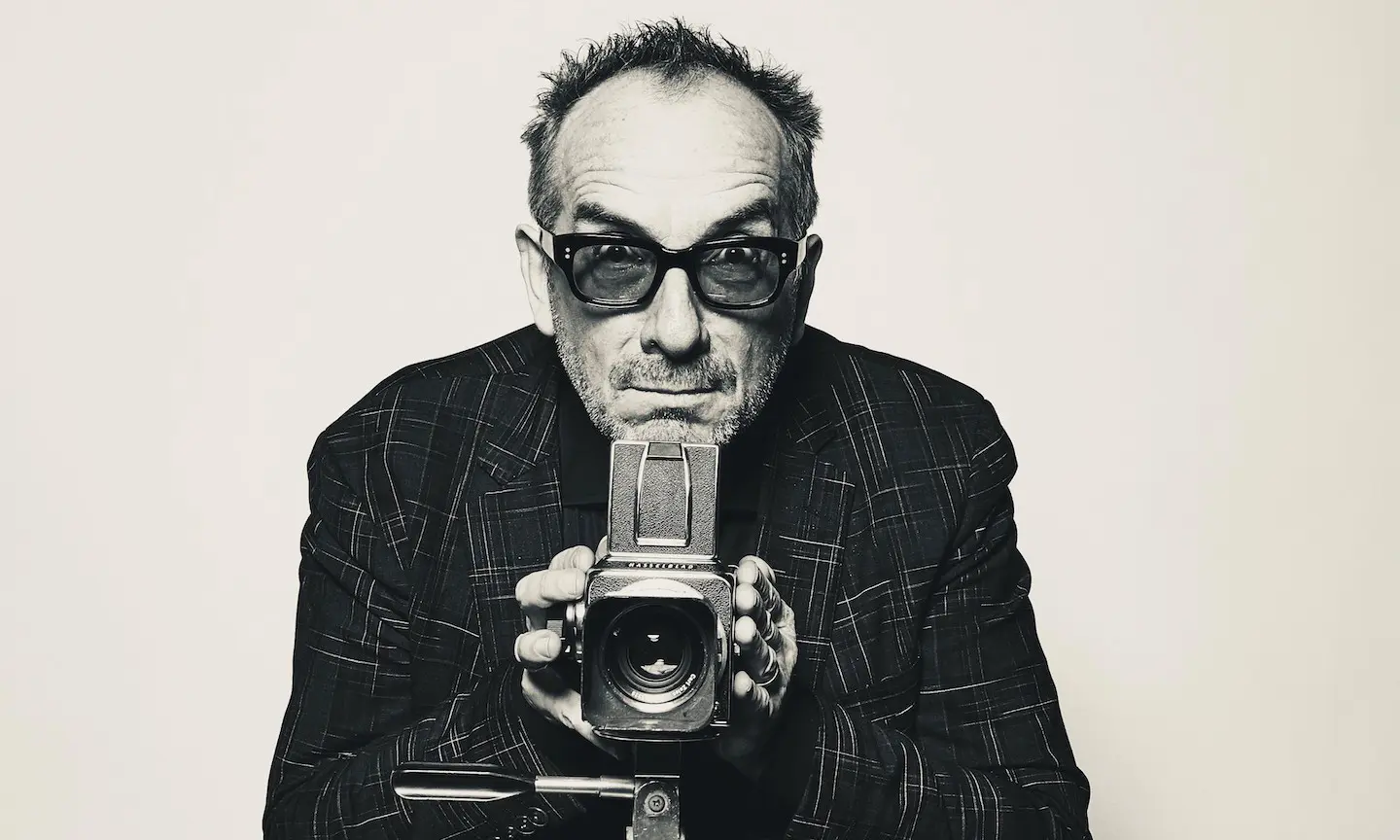

We caught up with both Costello and Krys about the original, groundbreaking 1978 album and how Spanish Model came together.

How was the idea of Spanish Model originally presented to you?

Krys: He [Elvis] just called up and said “I have this idea I want to do. I want to redo ‘This Year’s Model,’ take my voice out and put new singers in, and I want to do it all in Spanish.” I just looked at my phone for about 15 seconds and tried to process that. But I thought it was a crazy enough idea that it just might work. If you know any of Elvis’ work, you know that he doesn’t always do what you want him to do as an audience member. If you accept that and go along for the ride, you find some wonderful music – things like ‘Painted From Memory’ and ‘The Juliet Letters.’

You managed to make it sound like Elvis and the Attractions are playing with the new singers in real-time. What sort of magic did that require?

Krys: I’m a big fan of the original record, and the engineering and production that Roger Bechirian and Nick Lowe did. So when I started, I tried to mimic the original mix and found out two things: One, it didn’t work and two, I couldn’t do it. So when I let that idea drop and decided I needed to mix the songs around the new vocals and make them work for the singer and their interpretations, it all came together.

When you do a project like this, you’re bound to get some backlash from people thinking you can’t rework an iconic album. I’m wondering if that might have even been part of the appeal?

Costello: I don’t keep any holy relics around in my house, so I’m not so precious about that. I love what people have brought to this, and that little bit of daring. If you know what I’ve done, you know that the minute someone puts the word ‘iconic’ in the same sentence with my name, I’m going to break out in a rash.

This may be a hard thing for Americans to appreciate but when we made that record [This Year’s Model], the sole extent of our master plan was to make a record that could compete with ABBA and Fleetwood Mac on BBC Radio. For a brief moment in late ‘77 and early ‘78, there was just the Boomtown Rats, The Jam, and us in the charts – the other contemporary bands would follow in short order. We wanted to get on the radio and guess what, there were single hits, though they never were in America. So we’re not disturbing anything sacred when it took American radio until 1983 to know this even existed.

Was there anything in particular about the Spanish language or about ‘This Year’s Model’ that made you feel they were compatible?

Costello: I wish I could claim that there was. But it was really a chain reaction that began with David Simon asking for “This Year’s Girl” for season two of ‘The Deuce.’ Somebody at HBO wanted a female voice for the second verse and I said, “Don’t you think they should be approximately the same generation as I was when I originally sang it, so it sounds like a dialogue?” Natalie Bergman did that job, and that’s when we discovered the tapes were in good order, and Sebastian could mix it and find other power in the tracks. Somewhere in that process, I made this leap into Spanish, having sensed when it felt like to hear a female voice change the perspective, and I thought maybe it could be another language. And logically I wasn’t going to say, “Hey, maybe we should do it in Serbo-Croat.”

Krys: From my perspective, I know a lot of these peoples’ careers and aesthetics, and maybe I’ll put somebody forward that I think aesthetically might fit. But Elvis was listening to more purely from the vocal standpoint, so it was a good back and forth.

Costello: As I understand it, there’s a huge tradition in the Spanish-speaking world of ballad singing, therefore stories and lyrical perspective are very key. I didn’t want anybody because they were in the charts, or they saw a novelty to this. I wanted them to take the job seriously, and then have as much fun doing this as they possibly could. That’s certainly the principle of the early work I did with the Attractions, to care with your last breath and not give a damn at the same time.

I assume that the lyrics aren’t necessarily literal translations. Were there occasions where the meaning of a song would get changed or updated?

Costello: Only in the sense of getting the essence of a lyric. The very first one delivered was Cami’s “La Chica de Hoy,” which literally means “the girl of today.” It still contains the same idea, it means “it girl,” or “girl you’re all looking at.” What then becomes very different is that Cami is the person that people are looking at, in that particular moment of her career where she has emerged.

All those assumptions about what part of your appeal is the way you look, against what might be in your head and your heart – all that is in play in her own life and career, and I think that’s why she sang it so well. The most radical change is “Radio Radio,” because I wouldn’t have wanted Vito to be fighting a battle we were fighting 40 years ago, it would have made no sense. Mass communication has changed and he reflects that in his lyric – not as a manifesto, in a more good-natured kind of way.

What about ‘Chelsea’ and ‘Night Rally,’ which refer to specific aspects of London in 1977?

Costello: I’ll point out that those were the songs Columbia removed from the original American pressing, because they thought them too specific. “Night Rally” is an interesting one, it was written about the dread of the rise of the far-right in London, and I projected that onto a fantasy of what was happening. But for most of the Latin American artists, anyone who is approaching my age remembers Spain under a fascist dictatorship. So you don’t have to be a history student to have a sense of what that song implies.

Krys: “Chelsea” is very similar, you could apply the sentiment to today’s Miami.

Costello: If the song had been written in the 30s, it would have been about Hollywood. It’s about being from the nowhere place, and the dream and the compromise that comes with it. Originally “Chelsea” was written about a 1960s movie about an English girl who comes to London and gets involved in the fashion scene. That inspired it as much as anything happening in the contemporary world.

But at the same time, I was living in the London suburbs where nothing much was happening. I was traveling on the train to London every day to do my day job, which was funnily enough in a lipstick factory, at a cosmetic firm’s office. I wrote that song sitting at my little computer, thinking what it might be like to be that girl from the north of England coming into the groovy scene in London, which could be Miami or Hollywood, or any place where it’s happening and you’re not. You’re sort of saying “I don’t want to go there,” even though you don’t really mean it. You want to go there to find out what it feels like.

source https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/elvis-costello-spanish-model-interview/